The Altamira bronzes

Many of the pieces that are preserved today are of accidental origin or the result of furtive excavations. The scarce information available means that this site remains largely unknown, given that the scientific results of the excavation campaigns were never published. Furthermore, most of the finds lack an archaeological context and a chronology based on the use of parallels had to be used, which allows us to date the bronzes to between the 1st and 4th centuries AD. The remains of slag and raw metal ingots point to the probable existence of a smelting workshop in the castro where these pieces were produced. The bronze figures found in the hillfort, all of which are small in size, were cast using moulds and may have been used as votive offerings, i.e. as a commemoration of a vow or promise for some grace received. All of them appear broken and fragmented, which could indicate that they were intended to be remelted.

Hand with forearm

Right arm of a bronze sculpture cast in bronze. It is broken above the elbow and shows an outstretched hand with the thumb slightly bent inwards. The inner part of the arm preserves the remains of a cloak. The piece, which, despite its size, has good anatomical proportions and shows great technical quality, is hollow and must have been cast using the lost-wax technique.

Wing

Small, flat-bo7omed le= wing. It is in an unfurled position with the feathers marked by incisions. It could correspond to the figure of an Erote, that is, a god of love in Greek and Roman mythology, an equivalent of Cupid or Amore?. These deities were the companions of the god Eros and were dedicated to the complementary tasks of love. According to some myths, they were the children of Aphrodite; according to others, they formed part of her retinue.

Bovine

The back is well treated and the neck wrinkles are well marked. The eyes are incised and the head turns to the right. It is missing a horn, part of the two legs on the le= side and the start of the tail has been preserved.

This type of zoomorphic sculpture or ex-voto was interpreted as an offering or gift to the gods and as a substitute for sacrificial animals. The only type of animal represented in them are bovids, linked in some cases to oriental cults such as the Apis ox from Iria Flavia. The representations reflect the realis c anatomy of the animal.

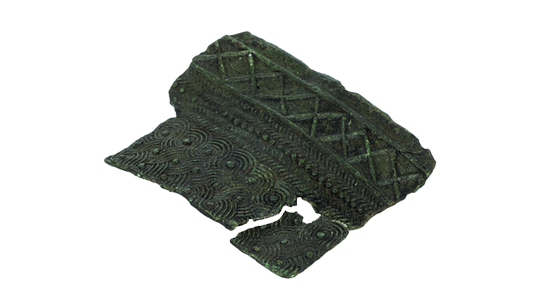

Fragments of sistulae

Sistulae are richly decorated metal vessels that are extraordinarily ornate and stood out in the castros for their high degree of technical sophistication. They were probably used for ceremonial banquets or other exceptional community celebrations. Given their size, it is thought that they are vessels that can be dated to between the 2nd century BC and the 2nd century AD.

A plate and a support for a s le handle, both cast in bronze, were found at this site. All the surviving fragments of sitsulae coincide in their taste for ornate decora on distributed in horizontal and/or vertical bands in which the different motifs are framed.

Mercury

This mythological god was the son of Jupiter and Maulla Maiestas. God of the sea, his name is related to the La n word merx, -cis (merchandise). He is the god of cunning and intelligence, protector of travellers and merchants. As a messenger, Mercury is seen as the inventor of languages, the alphabet and weights and measures, essential for trade.

In the small bronze sculpture found in Taboexa, Mercury turns slightly to the right, and is depicted with his head wearing the petasus or winged hat - very worn - under which his hair is showing.

The figure has a face with incised, triangular-shaped, strongly marked eyes, and wears a chlamys (a short cloak) buckled over the le= shoulder, which falls in so= folds to the level of the knees. In the le= hand he would carry the caduceus (a staff with two cobras coiled and two small ones at the upper end, now used as a symbol of trade and medicine), and in the right, the pouch or marsupium, both of which are missing. The le= leg is broken at the knee and the le= leg is broken at the ankle.

Robed figures

These robed figurines represent a genie or protective spirit in Roman mythology. One of them wears a veil and toga, the other only a toga, the manly garment symbolising Roman citizenship. This toga-wearing figure is depicted with his head par ally covered by this garment or 'capite velato', an attitude typical of when the emperor or other distinguished personage officiated at a religious ceremony.

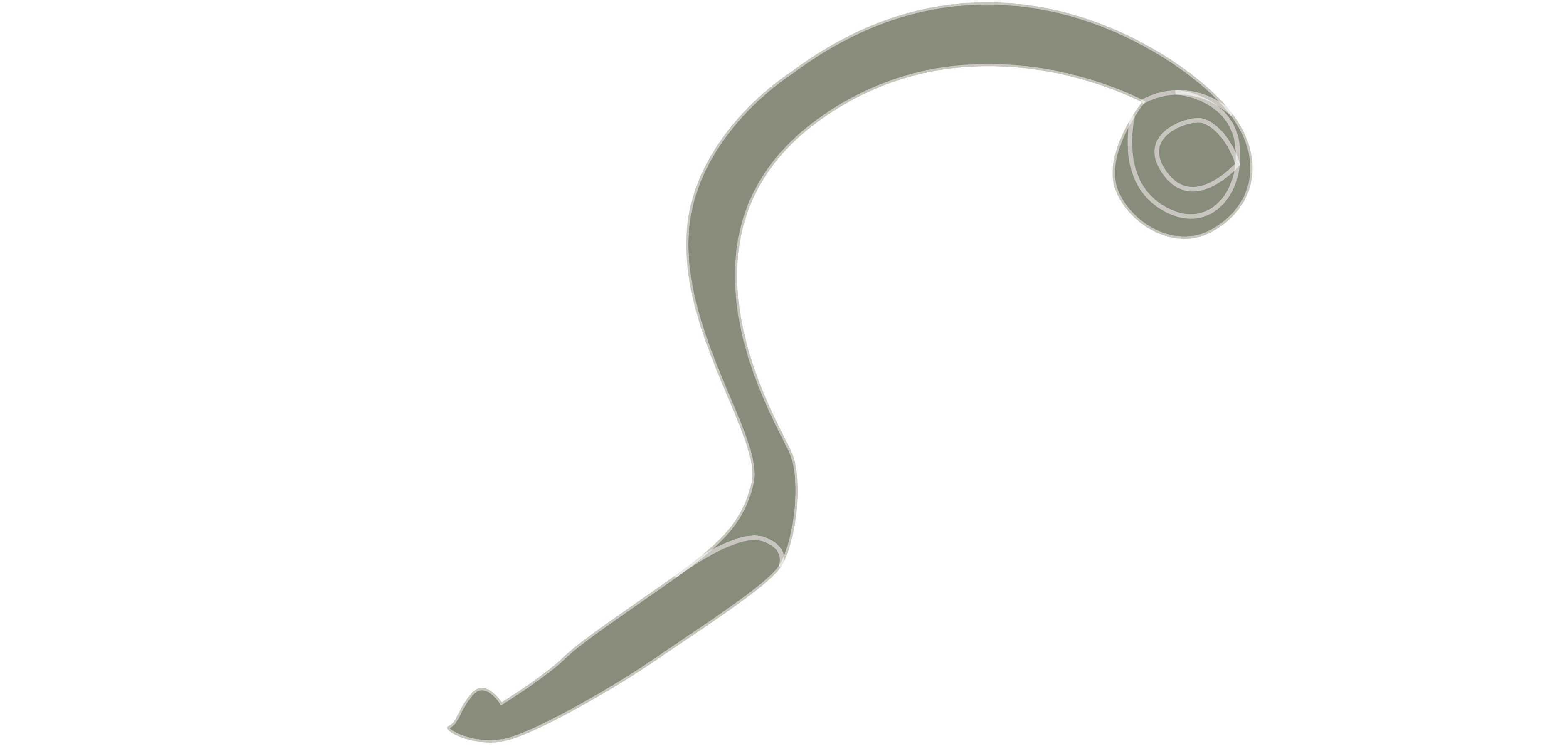

Fíbulae

A fibula from the 7th-5th centuries BC, of the Acebuchal type and with a straight foot, was documented at the Altamira hillfort. This type of fibula, with a curved bridge and straight foot, is typical of the Iron Age, specifically of the transition between the 8th and 4th centuries BC. They also appear throughout temperate Europe during the 5th century BC, which is evidence of the democratisation of their use. Specialists believe that this type of fibulae, from the Tartessian area, located on the Mediterranean side of the Iberian Peninsula, reached northwest Galicia through Phoenician or Punic trade to replace the double-spring fibulae.

Lucerne

The lantern found at Altamira is a Roman lamp that imitates the shape of a human head with blackish strokes. It is a small piece made of cast bronze with a greenish-brown patina. This piece has two qualities that make it stand out: its metalwork and its decorative theme. Both the material itself, bronze, and the technique used in its manufacture mean that it is more expensive than those made of ceramic, which are much more abundant.

Arula

The arulas are small hoops, bases or pedestals that support small zoomorphic sculptures or vove offerings that are interpreted as offerings or gallants offered to the gods as substitutes for sacrificial animals. The one found at Altamira is quadrangular in shape, hollow on the inside and finished with a smooth cornice. The upper part depicts a standing lamb joined by its legs, a tortoise with a reticulated carapace and marked head and legs. Next to it is a sign of another dubious figure, fractured at its base, which could be a scorpion.

Bronze foot

The foot is shod, broken a li7le above the ankle. The shoe's fastening straps were ed at the level of the joint between the leg and the foot by means of a lacing at the ends. The leather covering the foot, modelling the toes and heel, is very visible. The sole is also visible, so we could be looking at a calceus senatorius, i.e. a Roman boot ed with two pairs of straps that cross at the instep of the foot and go up to the middle of the leg, where they are ed with two knots. This type of footwear was exclusive to a certain social class, and was therefore not available to all the inhabitants of Rome.